Coastal First Nations’ connections to the sea and marine resources has never been fully acknowledged by new governments and regulatory authorities, thus preventing the ability for our First Nations to adapt their original marine resource economies of the day to benefit from participating in the current systems of commerce, trade, free enterprise and globally linked markets which now operate all around us. It is true that First Nations are participants in the ever growing marine economic sectors, but this participation is not in tune with how coastal First Nations would be involved (or ought to be involved) in the vast marine sectors of our region if our ownership / property rights and the right to resource stewardship control were ever acknowledged and upheld.

It should be noted that First Nations’ involvement in mainstream commercial economic activities such as logging and fishing has mostly been limited to employment as wage labourers. Due to multiple barriers, namely access to credit and capital, and oppressive Federal Indian Policy, First Nations were not granted the equal opportunity of participating in such industries as free willing capitalists, positioned to reap the benefits of their business investments; instead First Nations were generally inputs to the production processes of major corporations and private industry which for extensive periods have enjoyed excessive profits.

The history of First Nations’ commercial fishing licenses and asset disenfranchisement is one particular example that has widespread implications for the present day reality of many Fist Nations. The level of commercial fishing licenses and assets held by individual First Nations members and even entire Bands today is far below what it should be. This is a significant barrier to reversing the reality and to begin growing First Nations participation in sustainable commercial fisheries to the point where this industry is once again a major contributor to the health and wellbeing of First Nations on the coast.

Prior to European contact, our people harvested migrating Fraser River sockeye and other salmon in Johnstone Strait by means and techniques that were both reliable and successful. Fish were harvested to serve populations much greater than the 3,000 Lekwiltok citizens of today. Weirs, traps, nets and other fish capturing devices were operated as recently as 1920. The harvesting efficiency in Johnstone Straight in the 18th Century could undoubtedly surpass that of the commercial sector that exists today. Although capable of significant harvest levels, these traps and weirs were situated near villages, which became problematic for the fishing companies who eventually succeeded in having them replaced with vessels; better suited for transportation to centralized processing locations, thus asserting European controls.

It has not been easy for our people to gain stakes in the commercial fisheries of today after having our traditional methods taken from us. The systemically racist policies construed and forced upon First Nations by the government of the day were engineered to deprive us of basic rights and freedoms to take from us the abundant resources of our Lands and waters. Despite the many obstacles our forefathers, with much persistence, gained entry into the commercial fishing license programs administered by the Government of Canada. Currently there are court cases that have emphasised that the government racist policies and management plans infringe on our Aboriginal title and rights. These cases along with other actions are substantial achievements of coastal First Nations peoples on the road to realizing equality and equity following invasive European settlements of the 19th and 20th centuries. However, there is much more work to be done in reconciling this historical reality.

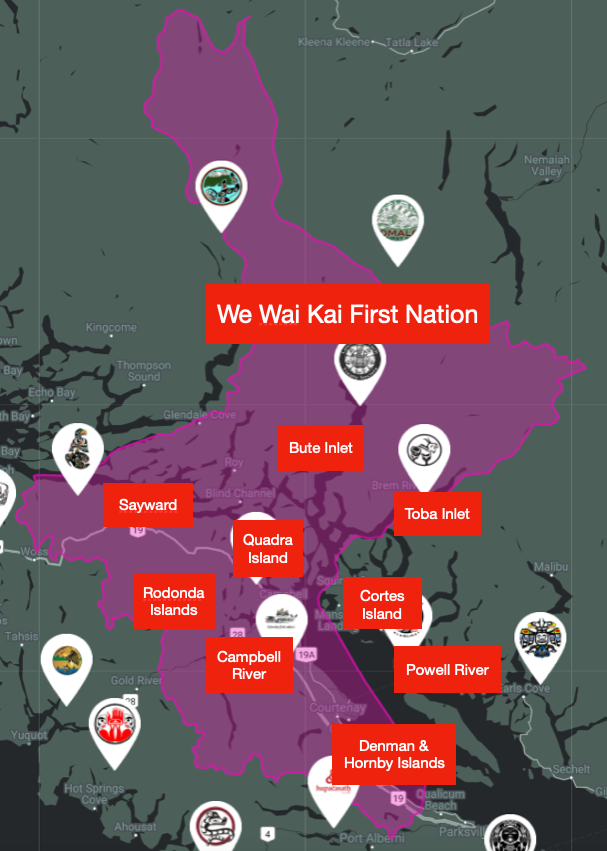

Serving the local fishing sector with affordable services and storage facilities: 2355 Spit Road, Campbell River, B.C.

The Wei Wai Kum Net Loft offers indoor and outdoor storage, two work lanes, forklift services, and a sheet wall for loading and unloading boats. The facility is run on a cost-recovery basis.